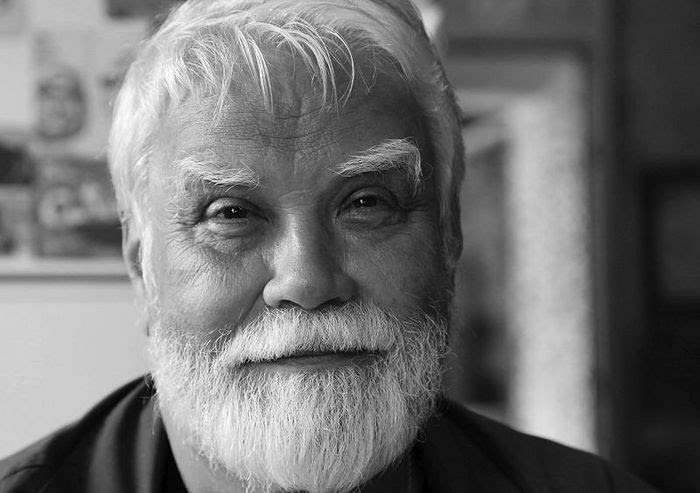

Priest Yaroslav Shipov. In the Afterworld, Awards are not Valued.

Andrey Samokhin

Source: Newspaper "Culture"

Фото: nikeabooks.ru

Фото: nikeabooks.ru

One of the laureates of the Patriarchal Award for Literature for 2016, which was presented recently in the Cathedral of Christ the Savior, was Archpriest Yaroslav Shipov. Readers have long known his wonderful short stories: simple and perfect in form and language. He was a recognized author back in the late seventies and head of the prose department in the "Contemporary" publishing house, then he unexpectedly became a priest in a remote village in Vologda in 1991 and abandoned writing and his beloved hunting. After serving there for about four years and restoring four parishes in the district, he returned to Moscow for reasons of health. And now he serves at the Patriarchal metochion in Zaryadye and continues to write. The newspaper "Culture" interviewed the prose writer.

What is the difference between this award and those you received in the past as a secular writer?

By what I now firmly know: neither medals nor premiums are valued there (points up). I, of course, am grateful to His Holiness and the jury for such a high appraisal of my very modest work. Now I can once again go fishing to Astrakhan. I am also grateful that I met with my old friend Viktor Likhonosov at the award ceremony, whom I had not seen for thirty years. I am very glad that they noted his work, he is truly a great artist...

Written literature in Russia began as a preaching work with the "Sermon on Law and Grace" of Metropolitan Hilarion, and it only much later acquired a secular dimension, departing from its origins. Can you imagine a point at which they will merge again?

In my personal situation, they come close to each other, although they do not merge. Preaching and literature are different hypostases, but you do not need to oppose the word-logos with the word-art. The Lord gave us the Holy Scriptures for survival and spiritual growth. And good literature helps to approach this. The language of the parables of the Gospel, for example, cannot be understood if you have not read anything before this except for comic books. Why, after all, did God give art to mankind? To sing unto the Creator and His creation. It is necessary to awaken the soul, to tune it so that it could at least remotely feel the breath of the Holy Spirit.

Literature, like any art that we call "classic," has a clearly pronounced religious origin. Since ancient times, only in Christian churches has it been customary to glorify God in word, music, and images, while this is not the case in other world religions, and sometimes it is even forbidden. Italy, Spain, and Portugal gave a start, followed by almost the whole of Europe. We entered upon this path in our own way: from Byzantine iconography, temple architecture and singing, and the lives of saints. Secular art began to develop with us somewhat later. But by the nineteenth century, a powerful surge of creativity in all types of art had begun in Europe. Art appeared even where it had never existed before. And also in Russia, of course, that century (as well as into the twentieth century) became a peak: in painting, in music, and in literature. For me, Tchaikovsky and Pushkin are unrivaled peaks in the last two spheres.

And then everywhere, and also almost at the same time, everything went into decline. It seems that the reason was in the impoverishment of faith. Artists, musicians, poets began to deliberately warp the divine harmony and even turn to demonic powers. As a result, without a living source, the roots of creativity dried up and flowers and leaves shriveled.

However, we, nonetheless, had in the last century, up to its middle, and even the last quarter, great writers, poets, and artists. It is enough to name Sholokhov, Leonov, Rasputin, Pasternak, Zabolotsky, Sviridov...

Yes, the decline of our creativity, despite the atheistic power, was slower than in the West. But we also did not avoid it. Although even today, with the deplorable, as it seems to us, spiritual state of our society, it is more alive than western society. Our country is probably the only one where temples are built not destroyed and where people still pray in them.

Perhaps the appearance of such books as "Everyday Saints" by Bishop Tikhon (Shevkunov), "The Procession" by Krupin, and your stories will return literature to its evangelical origin?

Everything that you mentioned is literature. A sermon has other tools and tasks. Let's take my example: the priesthood is a ministry but writing is also a ministry. And as you know, you cannot swear allegiance to two masters...

But this is not God and mammon, there is no dichotomy...

Of course; however, there is an old ecclesiastical expression: the first is more important than the second. Therefore, I am a priest in the first place, and in this I already integrate my creativity. By the way, for ten years after ordination, I did not write anything. But my current stories have not turned into sermons; this is another genre. It happens that the word of the shepherd, which ignites hearts from the amvon, causes only bewilderment when it is transferred onto paper: what could be captivating? On the other hand, recently many clergymen have began to publish their works. Unfortunately, not all of these authors understand what literature is. One priest called me and shocked me with the request: "Teach me to write well." "You need to," I said, "be nurtured by Russian literature all your life." He immediately became melancholy: "That's no good for me, I need to learn quickly." Well, he will scrabble something quickly and books will be published... As an editor with many years of experience, I can suppose that as early as the end of the 1980s, from the so-called "priestly prose," little would have been published by book publishers and in literary journals. And not because of censorship, since there already practically was none, but by professional criteria.

Are there for you, a priest and a writer in one person, any forbidden literary devices: hyperbole, irony, fantasy?

If you simply record reality without adding anything to it, you will end up with reports or journalistic essays. Of course, I use invention but very carefully: only to create a more vivid picture. In my youth, I easily invented stories and images. Today, some of these stories seem unconvincing to me and I have not included them in collections for a long time.

Do you use scenes from your own experience?

In most cases, yes, but some thoughts have to be developed, completed. I will give an analogy from another kind of art. The artist draws from nature only studies, sketches. But he creates a completed painting later in the studio. What you see must be passed through the soul...

In your opinion, is the formula "development of literature" that is favored by critics appropriate?

Hardly. Where have we developed from Pushkin, Gogol, Chekhov, or, say, Leskov? If we could get closer to them, but we haven't been able...

In the word "art (iskusstvo)," people sometimes identify "temptation (iskus)" as the root, which is alarming to the Orthodox ear.

The artistic gift, in any case is from God, which is also fixed in our language. But the artist is also given from above a free choice: to whom will he subordinate this gift, whom will he serve in the end: the Lord or the wicked one. This is not an easy task: many great artists were balancing on the verge their whole lives. The Apostle Paul warned: "See then that ye walk circumspectly." This applies to writers, probably, first of all, because every word will have to be answered for at the Last Judgment.

Translated by Aleksander Brooks